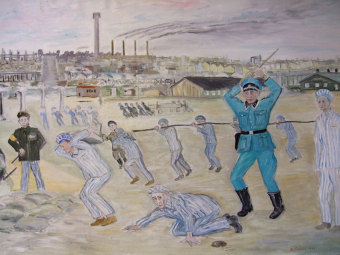

Punishments and Executions

© Benjamin Grünfeld

© Benjamin Grünfeld

“In cases of infractions of the rules by inmates, the I.G. foremen sent written requests to the S.S. administration for suitable punishment. The S.S. complied, recording on its own forms the details of the I.G. charge and the S.S. disposition. Typical offenses charged by I.G. included ‘lazy,’ ‘shirking,’ ‘refusal to obey,’ ‘slow to obey,’ ‘working too slowly,’ ‘eating bones from a garbage pail,’ ‘begging bread from prisoners of war,’ ‘smoking a cigarette,’ ‘leaving work for ten minutes,’ ‘sitting during working hours,’ ‘stealing wood for a fire,’ ‘stealing a kettle of soup,’ ‘possession of money,’ ‘talking to a female inmate,’ and ‘warming hands.’ Frequently reports included the I.G. foreman’s recommendations of ‘severe punishment.’ The response of the S.S. could be forfeiture of meals, lashes by cane or whip, hanging, or ‘selection.’”

(Joseph Borkin: The Crime and Punishment of I.G. Farben (New York: Free Press/Macmillan, 1978), p. 125.)

The dealings of the SS, and of many I.G. Farben employees and prisoner functionaries, were characterized by arbitrariness and continual threats of punishment, including the gas chamber at Birkenau. The SS created a world utterly devoid of rights, a system of terror in which murder and brutal physical abuse were features of the prisoners’ daily life; this situation produced an enduring climate of fear.

In the initial period of the Buna/Monowitz concentration camp, the SS employed Strafsport (punitive sports) to harass and exhaust the prisoners. In addition, “games” were played with the inmates’ lives, such as the “cap toss”: An SS man would throw a prisoner’s cap outside the cordon of guards; if the inmate ran to pick it up, the SS man would shoot him “while attempting to escape.” That paid off for the SS man, because he was awarded several days of leave for each “prevented escape.” Kapos might mistreat prisoners out of caprice: “In the case of the so-called neck seesaw, a cane was laid straight across the prisoner’s neck, with the prisoner functionary standing on both ends. By shifting his weight from one leg to the other, he then ‘seesawed’ his victim to death. Bonitz, who among other things was deployed as Oberkapo of the Buna detachment, was accused of at least 50 such murders by former inmates.”[1]

The plant management tried to curb capricious punishments, which did not contribute to the prisoners’ productivity, but the managers proceeded basically from a belief that the desired job performance on the inmates’ part could be attained only by goading, beating, and punishing them. The former prisoner Arnest Tauber reports that I.G. Farben construction supervisor Max Faust himself beat inmates at the construction site with a truncheon. Many German Meister, or master craftsmen, used the Kapos as an extension of their arms to make the prisoners work harder, and thus they passed on the pressure to meet completion deadlines. The Meister were required to report the prisoners’ performance, measured in percentage terms based on a German laborer’s output, to the camp management. For less than 75 percent, or a single score between 50 and 60 percent, the prisoner received 10 to 25 blows with a cane; for repeated “poor performances,” he was transferred to a harder detachment. A score of 20 percent could mean death. Some master craftsmen always wrote down 75 percent, but others consciously made use of their power over the prisoners. The plant management frequently complained about the inmates’ “dawdling” and triggered selections by the SS of prisoners deemed “not fit for work.”

Besides work performance, the master craftsmen and I.G. Farben inspectors who were moving around the construction site also had to report any “offenses” committed by the prisoners. The most common punishment was up to 25 blows with a cane while bent over a sawhorse, often administered by prisoner functionaries in the presence of the SS. Many of the abused prisoners lost consciousness even before the corporal punishment was over. Entire work detachments also could have their food rations withheld, or a prisoner might be transferred to a coal mine as an especially severe punishment. Another punishment consisted of forcing a prisoner to stand in the narrow strip, 60 to 80 cm (23 to 31 inches) wide, between the electric fence and the second fence; civilians also were punished in this way for forbidden contacts with prisoners.

To monitor the inmates and prevent political and resistance activities, the SS made use of informers among the prisoners. If an informer was unmasked, death at the hands of the inmate community was impending. The Political Department attempted to force confessions out of prisoners who were under suspicion by beating them and hanging them from a pole. It also had available a Stehbunker, a punishment cell measuring 40 x 40 cm (16 x 16 inches) in which only standing was possible. It was accessible only from the top. A prisoner could be confined in it for up to eight days, being given food only every fourth day and led out to the toilet only once a day. As an official punishment to deter other prisoners, the SS held public executions in the roll-call square. In particular, prisoners caught in an attempted escape were hanged there. Many survivors will never forget the Jewish resistance fighters Nathan Weissmann, Janek Grossfeld, and Leo Diament, who were hanged in the roll-call square on October 10, 1944.

(MN; transl. KL)