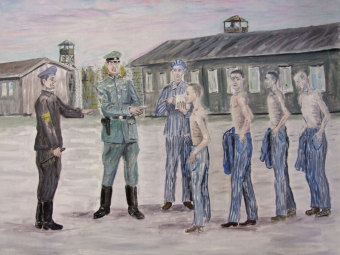

The Procedure for Selections in the Camp

© Benjamin Grünfeld

Selections in the Buna/Monowitz concentration camp took place in the blocks, at the roll-call square, or in the morning at the camp gate as the prisoners marched out. The selections in the blocks were undertaken after work and at intervals on the Sundays when inmates were off work, to keep I.G. Farben from being affected by loss of productive time. The sound of the gong announced the lockdown of the block. The block elder gave each inmate a slip of paper with his number, name, occupation, age, and nationality. All the prisoners in a block—as many as 250 men—had to crowd naked, except for their shoes, into the day room. Then, one by one, they had to go outdoors, where a committee made up of the SS camp doctor, the camp elder of the prisoner infirmary, the SS Sanitätsdienstgrad (SDG; hospital orderly), the block elder, and the block clerk awaited. The prisoner had to stop in front of the SS doctor, hand over his slip of paper, and turn around to make his buttocks visible—and show whether he still had any last reserves of fat there. Then he was required to return to the block. The prisoners tried to see which stack—“fit for work” or “not fit for work”—the SDG and the block clerk added their card to, at the instructions of the SS doctor. The inmates’ uncertainty and discussions about the decisions concerning them came to an end only one or two days later, at morning roll call, when the roll-call leader’s prisoner clerk called out the numbers of the men who had been selected. Shortly thereafter, the SS took them in trucks to the gas chambers of Birkenau. Usually their clothing came back only a few hours later, to be used for other prisoners.

The selections in the roll-call square took a similar course. The inmates had to step up by block and submit to a superficial inspection by the committee described above, and the numbers of those selected were recorded. Sometimes daily, sometimes at longer intervals—this probably was related to the number of complaints about the inmates made by I.G. Farben employees—selections were made at the camp gate as the prisoners marched out in the morning. The Arbeitseinsatzführer (work deployment administrator), the SS camp doctor, the roll-call leader, and the camp elder surveyed the prisoners as they marched past in rows of five, and pulled out those deemed “unfit for work.” Senior I.G. Farben employees, including the head of the Auschwitz industrial complex, Walther Dürrfeld, often took part in the selections at the camp gate, to ensure that the “right ones” were selected. Generally, 40 to 50 inmates were held back at the camp gate and subjected to an examination by the medical committee, and 20 to 30 of them were taken by the SS to Birkenau shortly thereafter.

The absolute number of selections in the camp can no longer be determined, owing to the widely varying estimates of surviving inmates and the incompleteness of the records available. The absence of benchmarks in the flow of camp life made a chronological ordering in people’s memories difficult. Thus accounts deal chiefly with unusually large selections like that of October 17, 1944, in which, according to the writings of Sonderkommando prisoner Zalman Lewental, 2,000 inmates were selected.[1] An inmate’s work area and the period during which he was a prisoner in Monowitz had an influence on the selections with which he was familiar. For example, prisoners working in the camp learned indirectly at most about the selections at the camp gate. The diverging information provided by survivors leads to the conclusion that the SS probably carried out a selection in the camp every four to six weeks, at minimum every three months.

(MN)