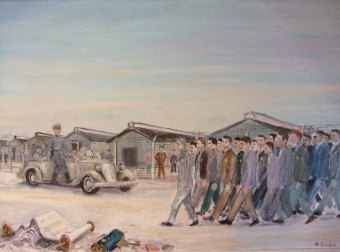

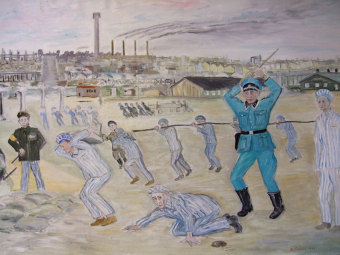

Benjamin Grünfeld: Pictures of Auschwitz

© Benjamin Grünfeld

Benjamin Grünfeld, deported from Cluj, Romania, to Auschwitz in 1944 because he was Jewish, survived, along with his brother Herman, a year of imprisonment in the Buna/Monowitz concentration camp under the worst possible conditions, the death march to Gleiwitz, and the so-called evacuation transports in open freight cars via Mittelbau-Dora to Bergen-Belsen, where the brothers were liberated by the British Army on April 15, 1945.

Even as a small boy, Benjamin Grünfeld loved to draw, and he says he has a photographic memory. The things he was forced to see and experience in the camp are still with him today; the images do not relinquish their hold. He has painted them for years on end. In pale colors and an apparently realistic style, he attests to persecution, brutality, and abuse. The pictures speak a clear language: He records his experiences, ranging from deportation to arrival at the ramp in Auschwitz-Birkenau to imprisonment in the camps of Buna/Monowitz, Mittelbau-Dora, and Bergen-Belsen. He seeks to give faces to those family members and friends who were murdered: In the moment of individual experience and suffering—selection, being hanged, being beaten to death at the construction site—they stand out from the gray mass of emaciated prisoners, are given a face of their own. Forming a contrast to the exhausted prisoners are the well-fed SS guards in uniform and a few prisoner functionaries, always a bit taller than the prisoners and with all the indications of a propensity to violence. The gray sky over the camp, always shown in horizontal stripes, reflects the glow of the flames in the crematoriums and apparently seeks to round off the nightmarish setting from above as well.

In the pictures, Benjamin Grünfeld emphasizes his own position as witness and survivor: He places himself in the paintings as an observer, identifiable by the faintly legible prisoner number on his arm, and he signs some by adding his prisoner number next to his name. Reduction of the realistic configuration of the setting to a documentary function would be a misapprehension: The pictures are an attempt at a documentation of the camp; above all, however, they challenge. They ask viewers to be willing to have the mediated notion of the psychological contingencies of concentration camp imprisonment held before their very eyes, and to understand the images as motivation for their own imagination and empathy. Benjamin Grünfeld’s pictures try to bear witness where words fail.

(SP; transl. KL)