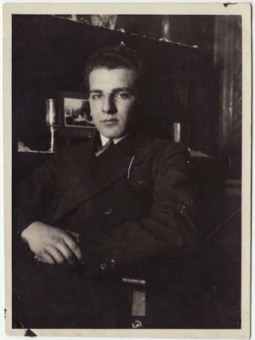

Norbert Wollheim’s Work in the Jewish Youth Movement (1926–1938)

© United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (Norbert Wollheim papers)

(Norbert Wollheim, Interview with Nikolaus Creutzfeldt [Eng.], New York 1986–88 (Heinlyn Productions; produced by Leslie C. Wolf). Archive of the Fritz Bauer Institute, transcript, p. 29.)

NW: No. No, I don’t remember any professor resisting because this is not a German concept. That concept of civilian citizens standing up to be counted did not exist in this way in the Germany of the times I remember.

Q: So there was never an occasion where a professor said, ‘Get out!’

NW: Well, Martin Wolff tried that and somehow they were a little astonished but it didn’t help too much.

Q: So the professor would leave the lecture hall?

NW: Small as Martin Wolff was, he wasn’t more than 5’6” or 7” with a powerful personality and he was respected even by non-Jews, so I remember the first time when a small group came in he could somehow paralyze them but then they came with more.”

(Norbert Wollheim, Interview with Nikolaus Creutzfeldt [Eng.], New York 1986–88 (Heinlyn Productions; produced by Leslie C. Wolf). Archive of the Fritz Bauer Institute, transcript, p. 35.)

(Norbert Wollheim, Interview with Nikolaus Creutzfeldt [Eng.], New York 1986–88 (Heinlyn Productions; produced by Leslie C. Wolf). Archive of the Fritz Bauer Institute, transcript, p. 45.)

(Norbert Wollheim, First Interview [Eng.], May 10, 1991. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, transcript, p. 18 [edited].)

(Norbert Wollheim, Interview with Nikolaus Creutzfeldt [Eng.], New York 1986–88 (Heinlyn Productions; produced by Leslie C. Wolf). Archive of the Fritz Bauer Institute, transcript, p. 54.)

Shortly after his Bar Mitzvah in Berlin’s Kaiserstrasse synagogue on May 1, 1926, Norbert Wollheim became a member of the German-Jewish Youth Community (DJJG; Deutsch-Jüdische Jugendgemeinschaft), a non-Zionist group that was part of the Jewish youth movement in Germany. The focal point of the youth movement was engagement with cultural and philosophical issues. In this process, the DJJG, founded in 1922, sought to organize Jewish life in Germany as part of German cultural life; in the words of one of its founders, Martin Sobotker, it saw itself as “the source of the duality of Germanness and Jewishness.”[1] In these years, Norbert Wollheim was influenced by the writings of Martin Buber and Franz Rosenzweig

The fundamental conviction that it is important to be involved in social causes and help those who are less fortunate than oneself was something Norbert Wollheim acquired at home. His father, Moritz Wollheim, was active in charitable organizations in Berlin’s Jewish community, especially in helping East European Jews in economically precarious circumstances, as well as the Jewish veterans of World War I. Norbert’s mother, Elsa Wollheim, also was involved in charitable organizations.

The teamwork with close friends in the DJJG had a decisive influence on Norbert Wollheim’s later life, and “out of this grew friendships that lasted over the years and even when we were all separated and people went to different countries, it bridged even oceans and countries.”[2] In 1931, Norbert Wollheim, like some of his friends from the youth movement, took up the study of law at the Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität in Berlin. In these years, the DJJG had begun to work together with the Central Association (CV; Central-Verein), not only in social activities, but also in campaigns against the growing anti-Semitism. At the Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität, the increasing strength of the National Socialists was more and more in evidence; they disrupted and prevented lectures by professors whom they considered Jewish or viewed as political adversaries, and threatened students. Norbert Wollheim did not know of a single non-Jewish professor who offered any opposition to this.

Now Norbert Wollheim intensified his work in the youth movement and for the social services of the Jewish Community of Berlin. After the Reichstag fire during the night of February 27, 1933, reprisals against Jews began to mount. The Central Association sent out helpers to visit Jewish families who had been attacked by Nazis. They were supposed to assist them, as well as to find out whether anyone had been taken away and what else had happened. One of these helpers was Norbert Wollheim.

Norbert Wollheim’s close friend Martin Sobotker was director of the Youth Care and Youth Welfare Department of the Jewish Community of Berlin in the years 1933–1939, and in summer 1933 he suggested organizing holiday trips to Denmark and Sweden for Jewish children, as such recreation was already banned in Germany. Norbert Wollheim picked up on the idea and was one of the escorts for the first youth group, which traveled to Denmark and Sweden in summer 1933. There they were warmly welcomed by the local Jewish communities.

In December 1933, the DJJG joined with other non-Zionist groups—the Hamburg German-Jewish Youth, the Jewish Youth and Children’s Groups of Berlin, the Jewish Liberal Youth Association, and the CV youth groups—to form the Ring, Federation of German-Jewish Youth (BDJJ; Ring, Bund deutsch-jüdischer Jugend). Norbert Wollheim became the secretary of the BDJJ; he also traveled to relatively small towns as a speaker, to lend moral support there. As of 1935, emigration was a increasingly urgent concern of the BDJJ and its members. Norbert Wollheim started working in a company that dealt in iron and manganese ore in 1935, in the hope that resulting contacts in other countries could be helpful with emigration.

In early 1937, the Ring, Federation of Jewish Youth was banned, but activities of the youth movement continued secretly, disguised as private meetings. Norbert Wollheim took part in them, as well as in public Jewish cultural life.

In the midst of this work, they received a call from Otto Hirsch in the Reich Confederation (formerly the Reich Deputation), saying that Great Britain was willing to take in Jewish children as refugees. Norbert Wollheim and others from the youth movement started to organize the Kindertransporte.

(MN; transl. KL)