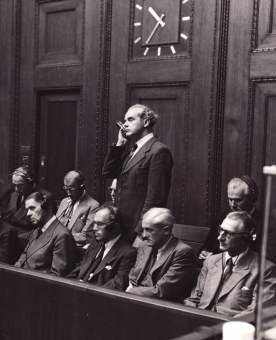

The Judgment in the I.G. Farben Trial in Nuremberg (Case VI)

© National Archives, Washington, DC

© National Archives, Washington, DC

© National Archives, Washington, DC

© National Archives, Washington, DC

The main trial ended on the 152nd day on which the court convened, May 28, 1948. Until sentence was passed on July 29 and 30, 1948, however, two more months elapsed. The cause of the delay may have been disagreements among the judges, which took the form of a dissenting opinion[1] by Judge Paul Macarius Hebert that was appended to the decision. Hebert joined the other justices in signing the judgment, however, despite his reservations, so that it would become operative immediately.

On counts one and five (planning and preparation of a war of aggression and acting as leaders of a conspiracy to commit crimes against peace), the judges accepted the arguments of the defense and acquitted all the defendants. The prosecution’s attempt to prove that the accused were aware “that rearmament was a component of a plan of aggression or that its object was the waging of wars of aggression”[2] was, on balance, a failure. Consequently, participation in a joint conspiracy to commit crimes against peace also could not be imputed to them.

On the other hand, the court found the charge that the I.G. Farben managers had appropriated private property in the occupied areas (count two: plundering and spoliation) proven on several points, in particular with reference to the conglomerate’s actions in Poland, Norway, Alsace-Lorraine, and France. The nine defendants Hermann Schmitz, Georg von Schnitzler, Fritz ter Meer, Max Ilgner, Ernst Bürgin, Paul Haefliger, Friedrich Jähne, Heinrich Oster, and Hans Kugler were found guilty of active participation in these crimes.

On count three (crimes against humanity and slave labor), all three judges rejected the charge that the accused had been accomplices or accessories to the mass murders and medical experiments; regarding the employment of foreign forced laborers, prisoners of war, and concentration camp prisoners, the judges viewed as proven the charge that the accused, in the case of I.G. Auschwitz and Fürstengrube, had acted on their own initiative rather than in obedience to superior authority: for the I.G. Farben management, there “existed from the very outset a plan […] to satisfy manpower requirements by adding concentration camp prisoners to the workforce.”[3] Moreover, the court agreed that the conglomerate had used concentration camp prisoners at its “own instigation,”[4] and that the utilization of prisoners had “taken place in full awareness of the poor, indeed inhumane, treatment.”[5] Hence those directly responsible for the site, namely Otto Ambros, Heinrich Bütefisch, and Walther Dürrfeld, as well as Carl Krauch and Fritz ter Meer, must be held accountable.

With regard to count four (membership in the SS), the judges were unanimous in their decision to acquit the three managers accused on this point: Christian Schneider, Heinrich Bütefisch, and Erich von der Heyde.

The sentences pronounced on July 29 and 30, 1948, were quite light, as measured against the seriousness of the charges: Thirteen defendants received prison sentences, and ten were acquitted. The heaviest sentences (eight years in prison for Otto Ambros and Walther Dürrfeld) were given to those convicted on count three (enslavement and mass murder), and for plundering and spoliation (count two) the accused were sentenced to terms ranging from one and one-half to five years.

Paul M. Hebert, disagreeing in part with the majority opinion, filed a dissent arguing primarily that the I.G. Farben managers’ defense of “necessity” did not apply: “The record shows that Farben willingly cooperated in the slave labor program in pursuit of a cardinal policy with the assent of the TEA [Technischer Ausschuss, Technical Committee] and the members of the managing board […].“[6] Subsequently, however, Hebert and alternate judge Clarence F. Merrell also disagreed with the acquittal on counts one and five (preparing and waging wars of aggression and conspiring to commit crimes against peace).

(SP; transl. KL)