The Feature Film La Tregua (The Truce) (Italy/Germany/Switzerland, 1997, directed by Francesco Rosi)

© Daniel Zuta, Filmproduktion

“You who live secure

In your warm houses

Who return at evening to find

Hot food and friendly faces:

Consider whether this is a man,

Who labours in the mud

Who knows no peace

Who fights for a crust of bread

Who dies at a yes or no.

Consider that this has been.”

“But only after many months did I lose the habit of walking with my gaze fixed to the ground, as if searching for something to eat or to pocket hastily or to sell for bread; and a dream full of horror has still not ceased to visit me, at sometimes frequent, sometimes longer, intervals. It is a dream within a dream, varied in detail, one in substance. I am sitting at a table with my family, or with friends, or at work, or in the green countryside; in short, in a peaceful relaxed environment, apparently without tension or affliction; yet I feel a deep and subtle anguish, the definite sensation of an impending threat. And in fact, as the dream proceeds, slowly or brutally, each time in a different way, everything collapses and disintegrates around me, the scenery, the walls, the people, while the anguish becomes more intense and more precise. Now everything has changed to chaos; I am alone in the centre of a grey and turbid nothing, and now, I know what this thing means, and I also know that I have always known it; I am in the Lager once more, and nothing is true outside the Lager. All the rest was a brief pause, a deception of the senses, a dream; my family, nature in flower, my home. Now this inner dream, this dream of peace, is over, and in the outer dream, which continues, gelid, a well-known voice resounds: a single word, not imperious, but brief and subdued. It is the dawn command of Auschwitz, a foreign word, feared and expected: get up, ‘Wstawać’.”

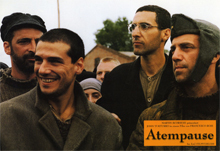

Primo Levi’s literary account of his journey from Auschwitz to Italy, La tregua (The Reawakening), was filmed in 1997 under the direction of Francesco Rosi. It is available in Italian with English subtitles.

The feature film “based on the novel” begins with opening credits in which the historical circumstances underlying the dissolution and “evacuation” of the Nazi concentration camps are introduced. The action begins with the decampment of the SS, and next Russian soldiers liberate a large number of prisoners, both men and women, emaciated and dressed in rags. With big, dark eyes and a guarded aloofness, the leading character, Primo Levi (John Turturro), observes the happenings and the subsequent uncoordinated transports, treks on foot, and stays in various Red Army camps on the way back to his native Italy. Comments on individual stops on the long journey of several Italian DPs through Poland are given by voiceover, using short passages from Levi’s text.

The film focuses on reawakening relationships among the survivors in a war-torn area. It shows the relationship of Primo Levi to the men with whom he travels long distances on the trip through Poland and the Ukraine: Ferrari, a petty thief; the shrewd Cesare; the grieving Daniele; the self-appointed commander, Rovi; and the inscrutable Greek, Mordo Nahum. They all want to get back home. As the journey proceeds, various short- or longer-term love relationships develop, and the main character, too (in a deviation from the book’s plot), has a short love affair with a woman formerly forced into prostitution at the Buna/Monowitz concentration camp. The longing for a return to life that is thus depicted is interrupted by several black-and-white flashbacks offering a glimpse of the time in the camp. The film does not address the grave consequences of imprisonment or even flesh them out, however; the diseases from which Levi suffered as a result of his time in the camp go unmentioned, as do his observations of lack of emotion and traumatization. The main character in the film appears merely melancholy, thoughtful, and pensive.

The end of the film La Tregua makes an effort to resolve uncertainties: The return home gives the impression of a happy end; the speaker concludes with a few words from Levi’s poem “If This Is a Man,” which make a general appeal not to forget what has happened.

In cinematic terms, Rosi tries to get as close as possible to the perspective of the man experiencing the events; the camera often is at eye level with Levi and illustrates, for example, his position—felt to be subordinate—with respect to the liberators on horseback riding down the road in Monowitz, or in relationship to the Greek Nahum, bursting with energy, his companion on the first leg of the journey. The film score serves up only a few, catchy melodies, whose sounds of string instruments or panpipes are reminiscent of a melodrama. They are a good match for the images, in which foggy, wintry tones of blue and green predominate; in terms of aesthetics and content, the reflective literary account of Primo Levi’s experiences is shifted in the direction of a moody, poignant odyssey with an ultimately hopeful outcome.

(SP; transl. KL)