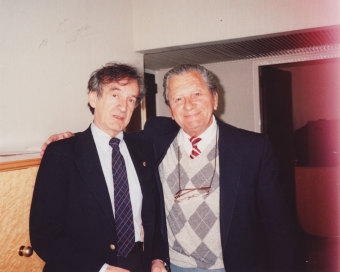

Elie Wiesel (*1928)

© Ya’acov Handeli

(http://www.eliewieselfoundation.org/aboutus.aspx (accessed on September 9, 2008).)

(Elie Wiesel: All Rivers Run to the Sea. Memoirs, vol. One 1928–1969 (London: HarperCollins, 1996), p. 380.)

“For me literature must have an ethical dimension. The aim of the literature I call testimony is to disturb. I disturb the believer because I dare to put questions to God, the source of all faith. I disturb the miscreant because, despite my doubts and questions, I refuse to break with the religious and mystical universe that has shaped my own. Most of all, I disturb those who are comfortably settled within a system—be it political, psychological, or theological. If I have learned anything in my life, it is to distrust intellectual comfort.”[1]

Elie (Eliezer) Wiesel, born in Sighet, Romania, on September 30, 1928, was the only son of Shlomo and Sarah (née Feig) Wiesel. He had two older sisters, Hilda and Beatrice (Bea), and one younger one, Tzipora. His grandfather, Reb Dodye Feig, was a deeply religious Hasid who had a powerful influence on young Elie Wiesel. With local teachers, he studied the Talmud and, against his father’s wishes, Kabbalah as well. Nonetheless, Shlomo Wiesel, a cosmopolitan businessman, insisted that Elie also learn modern Hebrew and read literature. In 1940, Sighet was returned to Hungary, and in spring 1944 the German Wehrmacht invaded the country. The Wiesel family was forced to move into the ghetto in Sighet. In mid-May 1944, the Jewish community of Sighet was deported to Auschwitz. After arrival there, the SS separated Shlomo and Elie Wiesel from the women. Elie’s mother, Sarah Wiesel, and his youngest sister, Tzipora, were murdered in Birkenau immediately after their arrival. Because Elie claimed to be older than his true age and Shlomo Wiesel younger, they were placed in quarantine in the Auschwitz main camp for three weeks and then assigned to the Buna/Monowitz concentration camp to do forced labor for I.G. Farben.

The father and son stayed together the entire time and tried to provide mutual support. They had to do heavy labor, including loading engines and rocks. The brutality and daily killings in Buna/Monowitz and at the I.G. Auschwitz construction site left Elie Wiesel’s religious faith profoundly shaken, and this is expressed in his subsequent accounts of life in the camp. As the Red Army approached Auschwitz in January 1945, the SS decided to evacuate the camp. At that time, Elie Wiesel was in the infirmary because of a foot injury; his contacts had enabled him to smuggle his father in there as well. As they assumed, however, that the SS would kill everyone who was left behind, they decided to join the march with the other prisoners.

With other Jewish youths, he was placed in orphanages, first in Écouis, then in Ambloy, and finally in Versailles. In France, he learned that his two older sisters, Hilda and Bea, also had survived. Elie Wiesel started learning French, the language in which he continues to this day to write. He studied at the Sorbonne and began working as a journalist, first for the Irgun, and then for Yediot Ahronot for many years. Still stateless, he managed nonetheless to travel frequently. On a trip to Brazil in 1954, he wrote his memoirs of the time in the Buna/Monowitz concentration camp in Yiddish, ... און די וועלט האָט געשוויגן (…Un di velt hot geshvign; And the World Remained Silent), published in Buenos Aires in 1956; a revised and abridged version, La Nuit (Engl. Night, 1960), appeared in French in 1958 and made Wiesel well known as a writer. In the years that followed, he wrote numerous novels, essays, and journalistic pieces, as well as speeches and essays on Hasidic scholars and biblical subjects.

In Paris, Elie Wiesel had resumed his Talmudic studies for several years, guided by Mordechai Chouchani, and later, in New York, he studied with Saul Lieberman for many years. In 1955 he went to New York, where he was granted U.S. citizenship. He taught there for many years at the 92nd Street Y and devoted himself increasingly to writing, finally giving up journalism for good in the 1960s. In 1965 and 1966, Elie Wiesel went to Moscow, and under the impression of his visits to Jewish communities in the Soviet Union he began to speak out internationally in favor of allowing Soviet Jews to leave the country. In the following decades, he repeatedly took up the cause of persecuted groups in every corner of the world. The knowledge that many people in Europe and the United States had kept silent about the genocide of World War II

In 1969, Elie Wiesel married Marion; Wiesel had met her and her daughter from a previous marriage, Jennifer, several years before through friends in New York. They had a son, Elisha. In 1978, President Jimmy Carter named Wiesel chairman of the President’s Commission on the Holocaust, renamed the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Council in 1980, after a trip to the extermination sites in Poland and the Soviet Union. Wiesel retained his chairmanship until 1986, spearheading the building of a Holocaust museum in Washington, D.C. The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum opened in 1993.

From 1972 to 1976, he taught in the Jewish Studies program at the City University of New York, and in the 1982/83 academic year, he served as a visiting professor at Yale University. Since 1976 Elie Wiesel has held a professorship in philosophy and religion at Boston University. He has received numerous awards, including the Grand-Croix de la Légion d’honneur (1984), the United States Congressional Gold Medal (1985), and the Presidential Medal of Freedom (1992). In 1986, Elie Wiesel received the Nobel Peace Prize, and shortly thereafter he and Marion Wiesel established the Elie Wiesel Foundation for Humanity.

In the United States in particular, Elie Wiesel has come to epitomize the efforts to commemorate the victims of the Holocaust. An iconographic survivor

Elie Wiesel lives in Connecticut.

(MN; transl. KL)