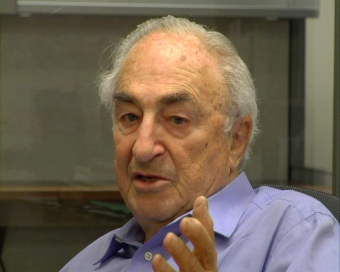

Ernest W. Michel (*1923)

© Fritz Bauer Institute

© Ernest W. Michel

© Ernest W. Michel

“I consider myself a lucky man. Not only did I survive, but I did so against all odds. More than anything else, I’m proud that I never gave up hope and that I was given the chance to rebuild my own life and participate in a meaningful way in the Jewish Community.”[1]

Ernst Michel, the son of cigarette manufacturer Otto Michel and his wife, Frieda, was born in Mannheim on July 1, 1923. His sister, Lotte, was born five years later. In 1936, on the basis of the Nuremberg Laws, he was no longer allowed to attend school. At first he was able to work in a factory that made cardboard packaging, not far from Mannheim, but the Jewish owners could no longer offer him employment after November 9, 1938. Numerous attempts to leave Germany met with no success. Not even the affidavit provided him by his American pen pal, Bob Lindsay of Wilmington, DE, helped him get out of the country: The line of people willing to leave Germany was too long, and the entry requirements for the United States were too tough. Only his sister, Lotte, succeeded in getting out, on a Kindertransport to France. The family’s living situation became increasingly worse, and his father was forced to sell his stamp collection piece by piece to keep the family alive. Finally, he was able to find an apprenticeship for Ernst, to train as a calligrapher. In early September 1939, the Gestapo came for him, to send him away for forced labor. He never saw his parents and his grandmother again.

In the four years that followed, he was confined in various work camps. In February 1943, with his friends from Paderborn, he was deported to Auschwitz and immediately placed in the Buna/Monowitz concentration camp. After a month of forced labor in the cement detachment, he was beaten up by an SS man. While standing in the waiting line in front of the prisoner infirmary (HKB, Häftlingskrankenbau), he had the great luck to be given a job as a clerk in the HKB because of his beautiful handwriting: That saved his life.

A short time later, he was assigned to work as a male nurse. In that job, his duties included carrying corpses and accompanying female prisoners to pseudo-medical experiments involving electric shock. Most of the women died from these procedures. Many of his friends died as well, but Ernst Michel, along with Honzo Munk and Felix Schwartz, withstood illness, hunger, and abysmal living conditions. On January 18, 1945, the SS forced them to go on the death march westward. They reached the Buchenwald concentration camp, where they were selected for mining work in Berga. On April 11, Berga, too, was to be evacuated, and the prisoners were forced to head east once more. They escaped from the column on April 18. After three days in the forest, they came to a place where they were given lodging in exchange for working on various farms, until they were liberated at last.

Ernst Michel wanted to go back to Mannheim. He failed to find a single family member there, and later he learned that his parents and grandmother had been deported, first to Gurs in France, and then murdered in Auschwitz in 1942. His sister, Lotte, survived the war in hiding in France, and she now lives in Israel. Ernst Michel was given a job with the U.S. Army and then worked as a correspondent for the German General News Agency (DANA, Deutsche Allgemeine Nachrichtenagentur) at the Trial of the Major War Criminals in Nuremberg. Though he could have continued to work for DANA, he emigrated to the United States in July 1946. There he worked at first as a typesetter for a newspaper, and in 1947 he took a job with the United Jewish Appeal (UJA). Here he changed his first name to “Ernest.” Over the years, he rose within this organization, finally becoming head of the UJA, headquartered in New York. In 1949, at a Jewish Federation singles dance, he met Suzanne Stein, whom he married in summer 1950. The couple had three children. Ernest W. Michel met Norbert Wollheim in the 1950s, and the two formed a long-term friendship. He took part in the distribution of the funds obtained in Wollheim’s settlement with I.G. Farben, allocating money to the former prisoners of the Buna/Monowitz concentration camp through Compensation Treuhand. In 1993, he published his memoirs, Promises to Keep: One Man’s Journey against Incredible Odds. Today Ernest W. Michel lives in New York.

(SP; transl. KL)

Ernest W. Michel, oral history interview

(English)