a “We came to Lübeck and went to the German Bürgermeister, to the mayor of Lübeck who had not been elected, he had been put into the position by the British because the British had occupied Lübeck on May 3. and we told him, ‘What about your commitment? Did you provide apartments or rooms for those people?’ And he said, ‘No, we have made provisions in a barrack for all these people to be accomodated.’ At this moment my friend and I looked at each other and he did something that is only understandable under the situation then. He afterall was an American soldier, though a staff sergeant. But he was in a territory occupied by the British. But he assumed a certain jurisdiction he wasn’t entitled to but in order to help it didn’t matter. He actually touched his rifle and told the mayor in Lübeck in no uncertain terms in German that they had made a commitment for people who had enough of barracks, who had lived for years under the most unbelievable conditions because the Germans wanted it that way. That therefore if he doesn’t fulfill his commitment, he would see to it that he will sweat it out in the jail of the Allies. And that fellow when he heard those words said, ‘Certainly he didn’t mean it that way.’ And this and that; so to cut a long story short, a bus with our people were waiting and then another bus was provided which went from apartment to apartment according to a certain list which had been prepared by the administration in Lübeck and we were all put as subtenants into rooms of German landlords. And this is how I came to Lübeck in June 1945. There I lived until I left for the United States in fall 1951.”

(Norbert Wollheim, Interview with Nikolaus Creutzfeldt [Eng.], New York 1986–88 (Heinlyn Productions; produced by Leslie C. Wolf). Archive of the Fritz Bauer Institute, transcript, pp. 164–165.)

b “I ask you a great favor for myself and the people here. Please neglect no opportunity to inform the people there to encourage or rather to arouse them. Two weeks ago we had a mass meeting in Belsen under the slogan: “Six million gassed Jews – World, where is your conscience?” This slogan is characteristic of the situation in which we are now living. We have been saved, but we are not liberated. We know that there are a number of Jews – we have met them there – who are so deeply moved by all they have seen and experienced that they will do everything in their power to make our voice heard. Help us with that. Help us to make it clear to everybody that we are waiting for many things which so far have not been realized. What do gifts of food rations or cigarettes or chocolate mean to us today! Certainly a valuable aid for which we are thankful, but the important thing is our desire that at least a place be found for us. It is this, which, in the last analysis, has given us the energy to pull through. Should it not be possible to find room at least for these 60,000 survivors away from this blood-drenched soil?”

(Norbert Wollheim, Letter to Hermann E. Simon, August 26, 1945 (English translation). USHMM, Wollheim Literary Estate, Box 9, Correspondence File, Simon Letters, pp. 1–2.)

c “Another difference between us and the American Zone was the fact that we had more tensions with the occupation authorities, since the British were acting against our interests in Palestine. I need only mention the

Exodus affair. So we needed a very special unanimity in our own ranks, and I must say that it worked splendidly.”

(Norbert Wollheim in: Michael Brenner: After the Holocaust: Rebuilding Jewish Lives in Postwar Germany (Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP, 1997), p. 98.)

d “There was still another job to be done in which I participated and that was, under the military statute, a so-called successor organization was built to claim the heirless and community property of the Jewish community. This was under Allied law with the seat in London and I became one of the founders and we were able then to solve the problems by putting all the funds which accumulated out of community property which was not used by new communities, and heirless property into one fund and this fund was administered by a mutual committee of the communities and the major Jewish organizations and then distributed especially for social purposes for needy people in Israel and in America, so that was the Jewish Trust Corporation and then I came to the United States.”

(Norbert Wollheim, Second Interview [Eng.], May 17, 1991. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, transcript, pp. 63–64 [edited].)

e “Q: Why did you decide to come to America? As opposed to England or Israel?

NW: Well, there were personal reasons.

I was looking for my friends and I was looking for my family. Because we had approxim[a]tely eighty or ninety members of my family. Because both my father and my mother had eight sisters and brothers. None of them survived except a cousin now living in Paris. And a cousin who had lived underground in Germany. That was all. So I was looking for people who were near and dear to me. I had a few relatives in the United States and I then found gradually the lost friends of my Youth Movement and others in the United States. And also I had acquired a better knowledge of English. Also my second wife was always together with a group in these years. Had a very close relationship with her sister. And the sister and her husband decided to come to the United States and my wife didn’t want to be separated from her sister. So that had nothing to do with ideological reasons. It was more personal reasons. I had come to experience the United States in ’46 when I was invited to come over as a so-called messenger of the remnants and had gone all over the country to speak to people and to give them an idea of the situation. So at this time I had solidified my relationship with the people I hadn’t seen for years and years. Including my Youth Leader, Marin Sobotka [Martin Sobotker].”

(Norbert Wollheim, Interview with Nikolaus Creutzfeldt [Eng.], New York 1986–88 (Heinlyn Productions; produced by Leslie C. Wolf). Archive of the Fritz Bauer Institute, transcript, pp. 180–181.)

In late April 1945, as the Red Army was advancing toward Berlin and the nearby Sachsenhausen concentration camp, the SS forcibly drove the camp’s prisoners on a northward march. During the night of May 2, 1945, Norbert Wollheim and several friends, including Albert Kimmelstiel, decided to escape from the column. The next morning, near Schwerin, they met American soldiers, one of whom was Hermann E. Simon, who knew friends of Wollheim in New York. Because Schwerin was part of the Russian zone of occupation, Simon advised them to go to Lübeck, which had seen relatively little wartime destruction. a Quite soon Norbert Wollheim became involved in helping to build a new Jewish community life in the British occupation zone.

As Norbert Wollheim recalled, there were about 800 Jewish Displaced Persons (DPs) in Lübeck in those days. Overall, around 15,000 DPs were living in the British zone in the postwar years, most of them in the Belsen DP camp. It was in Lübeck that Norbert Wollheim first learned of Belsen, and with the help of a Red Cross transport he managed to smuggle himself into the camp, despite his lack of a pass for travel within the British zone. There he met Josef (Yossele) Rosensaft, the chairman of the Committee of Liberated Jews in Belsen. Together they decided to found the Central Committee of Liberated Jews in the British Zone, and at its first congress on September 25–27, 1945, Josef Rosensaft was elected chairman, and Norbert Wollheim, deputy chairman. Wollheim was responsible for contact with the British occupation authorities. During this period he traveled to Belsen every week for organizational meetings; he told Hermann Simon, now out of the army and back in New York, about the living conditions and hardships of the DPs. b

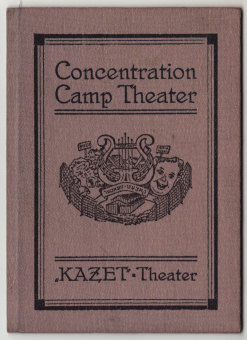

The following year, Norbert Wollheim was elected chairman of the Jewish Communities in the British Zone. In contrast to the U.S. zone, where a far greater number of DPs lived and to which thousands more migrated from East Europe in the years immediately after the war, the British zone saw close cooperation between the German and East European Jews in the resurgent communities and the DP camps. In addition to making arrangements for food, clothing, and medical care for the DPs, the work of the Central Committee of Liberated Jews in the British Zone consisted of establishing contacts with other DP camps and helping the survivors search for relatives. Aside from that, a new Jewish religious and cultural life emerged in the camps, and schools and theaters were founded.

The Central Committee was supported in its work by American and British organizations such as the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee and the Jewish Relief Unit. As part of his political work with British Jewish charitable organizations and his pursuit of political contacts in London to benefit the DPs, Norbert Wollheim made his first postwar trip to England in 1946; other trips followed. The same year, the United Jewish Appeal invited him to give talks in a number of U.S. cities about the situation of the Jewish DPs in Germany. In Germany, too, Wollheim made a number of public statements.

The core mission of the Central Committee, however, was to assist DPs who wanted to emigrate. “And we had accepted already that line that certainly the emphasis is that people want to go to then- Palestine, but also those who want to join their relatives in England and America should be given the opportunity as soon as possible to do this, because Europe is one big cemetery for us.”[1] Frequently this proved difficult, as the immigration quotas of many countries were quite small, and survivors suffering from diseases acquired in the camps often encountered additional difficulties in obtaining a visa. Many DPs wanted to emigrate to Palestine, but the restrictive policy of the British government regarding the “Palestine Mandate” made that virtually impossible. This conflict of interests led to numerous tensions between DP representatives and occupation authorities in the British zone. c The DP representatives supported the Aliyah Bet, the illegal immigration to Palestine. Only the founding of the state of Israel on May 14, 1948 (Iyar 5, 5708), made it possible for many DPs to emigrate. In August/September 1949, there were still about 3,500 DPs living in the British zone.

Norbert Wollheim also participated in the founding of the Jewish Trust Corporation for Germany, whose mission was to secure for Jewish successor organizations in the British zone the assets of the destroyed Jewish communities and assets without any heirs, in order to use them for social purposes. d In addition, he was involved in the redevelopment of permanent Jewish community structures in Germany. In August 1951, the Central Committee of Liberated Jews in the British Zone was finally disbanded. In September, Norbert Wollheim and his family emigrated to the United States. e “I left Germany when I thought the work was done. This didn’t mean only the closure of the camp but also the clarification of important questions concerning reparations and the restoration of Jewish life.”[2]

(MN; transl. KL)