a “It became clear to me that we were treated like beings that essentially are already dead. And the people who tormented us, seeking to prolong their own breathing time by compliance, dealt with this reality without any regard for fellow human beings. (Anyone who was seized by great despair quickly lost his personality.)”

(Imo Moszkowicz: Der grauende Morgen. Eine Autobiographie (Munich: Knaur, 1998), pp. 111–112. (Transl. KL))

b “Death had lost its normalcy for us because it had degraded us so boundlessly, this ultimate dominator of the world. Degradation—yes, that was the process that no longer permitted any kind of humane behavior, that stained the soul and the character, that left raw scars which never will heal. (Even Time, which heals all wounds, can provide no help here.)”

(Imo Moszkowicz: Der grauende Morgen. Eine Autobiographie (Munich: Knaur, 1998), p. 152. (Transl. KL))

c “I gladly admit that I am addicted to this ability to forget, which failed to operate only in the years when—after trembling through the night—I finally saw the dawn that signaled a beautiful day; then the sadness powerfully forced its way into my dreams and refused to accept my wish to know nothing more of it, battered my deepest unconscious, to which I believed I had banished the shreds of my past, safe from every grasp.”

(Imo Moszkowicz: Der grauende Morgen. Eine Autobiographie (Munich: Knaur, 1998), pp. 16–17. (Transl. KL))

d "The hideous face of hatred reveled in our humiliating situation, into which we had been drawn by the authority of the state, the will of the people, spurred by an antisemitism that was many centuries old. And since earliest childhood this question has floated in my brain: Why?”

(Imo Moszkowicz: Der grauende Morgen. Eine Autobiographie (Munich: Knaur, 1998), p. 18. (Transl. KL))

“(Even asking whether one situation or another had taken place in this or that way would bring me, in terms of health, to the limit of my possibilities.) I cannot let the time of the camps reopen again, I must forget it, otherwise I’ll die of it, retroactively. These lines alone are enough to rob me of my night’s rest. Please find an excuse for me if I concede justice no chance in these trials; a ‘life sentence’ cannot be an atonement.”

(Quoted from a letter from Imo Moszkowicz to Dr. Wenzky, October 12, 1960. (Transl. KL))

“We were ‘chained together’ like galley convicts, and it was these bodies, these hands, these eyes in the camp then; and they are still the same hands and eyes now, admittedly altered by civilization and freedom and aging, but ‘irradiated’ by Auschwitz. Here the past becomes physically close. Too close. Unbearably close.”[1]

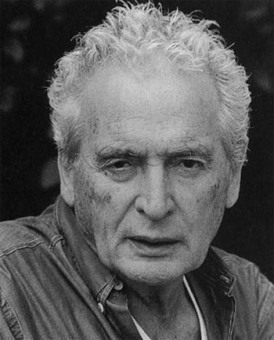

Imo Moszkowicz was born in Ahlen on July 27, 1925. His father, Benjamin Moszkowicz, who had been a Russian soldier in World War I, had settled there to work as a shoemaker after his release from war captivity. Benjamin and Chaja Moszkowicz had five sons and two daughters, and the family’s means were very limited. The father emigrated to Argentina in early 1938, and the rest of the family was supposed to follow, leaving Germany on November 10, 1938, but their apartment and the documents enabling them to leave the country were destroyed during the Night of Broken Glass (Reichskristallnacht, November 9 and 10, 1938). In fall 1939, the Nazis made the town of Ahlen judenrein, “free of Jews,” and the Moszkowicz family had to move to Essen. There, starting in 1940, Imo and two of his older brothers, Hermann and David, had to do forced labor. That saved them from being deported to Auschwitz in 1941, together with their mother and four other siblings. David was denounced after illegally going to a movie and was shot upon arrival in Birkenau. Imo and Hermann were the last in their family to be deported to Auschwitz, in 1942.

Imo Moszkowicz was admitted to the Buna/Monowitz concentration camp a , where he first did hard labor in the cement detachment and the carpentry detachment before managing to switch to a better work detail. There he met a Kammersänger and volunteered to perform at a “social evening” for the entertainment of the camp SS and prominent prisoners: this was his first brush with acting.

On January 18, 1945, Imo Moszkowicz was forced to take part in the death march. Finally the prisoners reached a subcamp of the Gross-Rosen concentration camp, where they were shut into a horizontal mining tunnel in which there was escaping gas. Many prisoners were killed in the ensuing mass panic; Imo barely escaped with his life. b In the chaos, Imo Moszkowicz and other prisoners separated themselves from the mass of refugees fleeing westward. Imo disguised himself as a member of the Wehrmacht and was liberated by the Red Army in Liberec (Czechoslovakia) in early May 1945. The only surviving member of his family, he returned to Ahlen.

In 1948, he became an assistant director for Gustaf Gründgens in Düsseldorf. c While working as a director, he met his wife, Renate, in South America. In 1961, he staged the first performance of a play by a contemporary German-speaking author in Israel: Zeit der Schuldlosen [Time of the Innocent] by Siegfried Lenz. In the FRG he also directed many well-known film productions, such as Max der Taschendieb (Max the Pickpocket) (FRG, 1962) and the Pumuckl movies (FRG, 1978; Germany, 1999). In 1998, Imo Moszkowicz published his autobiography, Der grauende Morgen (Gray Dawn), in which he shows how the memory of the Buna/Monowitz concentration camp repeatedly breaks unbidden into his later life. d Imo Moszkowicz died in Ottobrunn near Munich on January 11, 2011.

(LG; transl. KL)