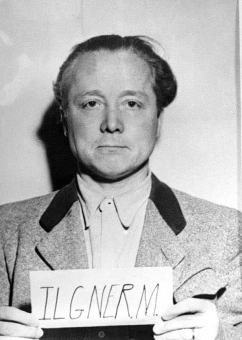

Max Ilgner (1899–1966)

© National Archives, Washington, DC

Max Ilgner was born on June 28, 1899, in Biebesheim. He was the son of a former soldier and BASF employee, Emil Ilgner, and his wife, Mathilde. After attending school in Düsseldorf, he entered the Haupt-Kadettenanstalt (Main Military Academy) in Berlin-Lichterfelde. He served in World War I and was on the Western Front at the war’s end in 1918. In 1919, he began the study of chemistry, metallurgy, law, and political economy at the Technical College of Charlottenburg and the University of Frankfurt am Main; in 1923 he received his doctoral degree, writing a dissertation on raw material supply in the German sulfuric acid industry. In addition, he completed training in commerce and banking. In 1923/24, he worked in Stockholm, where he met his future wife, Erna Hällström, with whom he had three children.

In 1924, Ilgner began his career at Cassella in the sales department, and in 1925 he was named director. In 1926, after the formation of the conglomerate I.G. Farben AG, he became an authorized signatory there. He later moved to the Central Finance Department at the Berlin N.W. 7 office, where he coordinated I.G. Farben’s industrial espionage through a network of employees abroad and gathered information, including data on industrial plants in foreign countries, that “served as a basis for determining targets for the Luftwaffe’s bombing.”[1] Moreover, he was a vice president of the American I.G. Farben. In 1934, he was named an alternate member of I.G. Farben’s managing board, and he became a full member in 1938. He had joined the NSDAP in 1937, and the following year he was made a “military economy leader” (Wehrwirtschaftsführer). He took over the running of the Buna plant at Schkopau in 1939. In 1941, he received the War Merit Cross 2nd Class (Kriegsverdienstkreuz 2. Klasse), and in 1945, the German Red Cross 1st Class (Rotkreuz-Ehrenzeichen 1. Klasse). Max Ilgner was a member of numerous supervisory boards of the firms taken over by I.G. Farben in the Wehrmacht-occupied regions of Europe[2] and part of the circle of economic leaders who worked with the Propaganda Ministry. He did all he could to create a positive image of I.G. Farben abroad.

In 1945, Max Ilgner was arrested by the U.S. Army, and he was indicted in 1947 in the I.G. Farben Trial in Nuremberg. He was sentenced in 1948 to three years in prison for “plunder and spoliation.”

(SP; transl. KL)