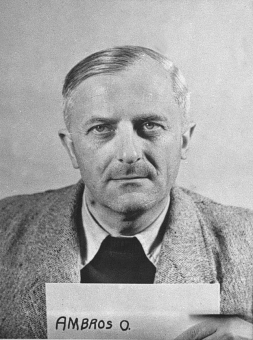

Otto Ambros (1901–1990)

© National Archives, Washington, DC

“I saw no charge that could be brought against me as an individual. It was the questioning by the Office of the Public Prosecutor that first pointed toward the matter of I.G. Farben’s Auschwitz plant, though initially I had no idea wherein my crime could lie.”[1]

Otto Ambros was born on May 19, 1901, in Weiden in the Upper Palatinate region. He joined a Freikorps (private paramilitary group) and served as a “temporary volunteer,” helping to suppress the revolutionary uprisings in Munich in 1919, in the Ruhr in 1920, and in Upper Silesia in 1921, supporting the German nationalists in the “Storming of the Annaberg” in opposition to the area’s incorporation into Poland. In 1920 he had begun studying chemistry and agronomy in Munich, where he worked under Nobel Prize winner Richard Willstätter and was awarded a Ph.D. in 1925. One year later, he started work in the Ammonia Laboratory of the BASF plant in Oppau. In 1930, he took a one-year study trip to the Far East. He was quickly promoted within the company, and in 1935 he managed the construction work for the first Buna plant in Schkopau.

On May 1, 1937, he joined the NSDAP (member number 6099289). In 1938, he was appointed to the management board of I.G. Farben, as a full member. In 1940, he became an adviser to the Department for Research and Development of the Four Year Plan, under I.G. Farben supervisory board chairman Carl Krauch: Ambros, the I.G.’s expert on poison gas and Buna, worked as a “military economy leader” (Wehrwirtschaftsführer) in the Chemical Weapons Section. In mid-May 1943, in a personal presentation at the Führer’s headquarters, he explained to Hitler the effect of the new German nerve gases tabun and sarin. The following year, he became managing director (plant manager) of Buna-Werk IV and of the fuel production facility in Auschwitz. Between 1941 and 1944, he visited the I.G. Auschwitz construction site a total of 18 times. Ambros was an active advocate of the use of concentration camp prisoners at the construction site, and on April 12, 1941, he wrote to an I.G. Farben director, Fritz ter Meer: “On the occasion of a dinner given for us by the management of the concentration camp, we furthermore determined all the arrangements relating to the involvement of the really excellent concentration-camp operation in support of the Buna plants.”[2] From his point of view, the Buna/Monowitz concentration camp represented a piece of luck for the prisoners.

In 1946, he was arrested by the U.S. Army, but for the time being was allowed to continue working for BASF in Ludwigshafen, in the French occupation zone. He was not delivered to justice until shortly before the I.G. Farben Trial in Nuremberg began. Ambros was found guilty of “enslavement” and “mass murder” in 1948 and sentenced to a prison term of eight years. He viewed the conviction as wrongful.

Released in 1951, by 1954 Ambros already held seats on numerous supervisory boards, including those of Chemie Grünenthal (where he was active during the Contergan scandal of 1961/1962), Feldmühle, and Telefunken. He worked as an economic consultant in Mannheim, and among the clients he advised were Federal Chancellor Adenauer and the industrial magnate Friedrich Flick. After his death in 1990, BASF paid tribute to him in an obituary as “[a]n expressive entrepreneurial figure of great charisma.”[3]

(SP; transl. KL)