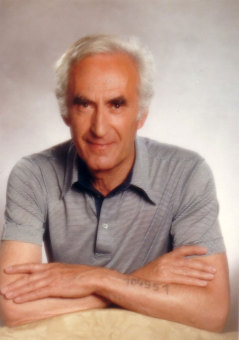

Paul Hoffmann (1921–2008)

© Daniel Hoffmann

© Daniel Hoffmann

© Daniel Hoffmann

Paul Hoffmann, born in Iserlohn on October 14, 1921, was the son of the hardware dealer Julius Hoffmann (born March 31, 1888, in Hohenlimburg, Westphalia, died on July 17, 1939, in Iserlohn) and Selma Hoffmann, née Weinberg (born May 25, 1889, in Breisach in the Breisgau region, died March 3, 1943, in the Auschwitz concentration camp). His sister Mathilde (born November 5, 1923, in Iserlohn, died November 12, 1973, in New York) emigrated on her own to the United States, aboard a ship that sailed on February 9, 1938.

Paul Hoffmann came from a lower-middle-class background. After four years in a Jewish primary school, he attended a Catholic middle school in Iserlohn from 1932 to 1936. In May 1936, he started a commercial apprenticeship in an Iserlohn clothing store, whose owner was also a Jew. He was forced to leave the apprenticeship on November 9, 1938. After the Night of Broken Glass, the Gestapo arrested Paul Hoffmann and kept him in confinement until December 12, 1938. After his release, he attended a Jewish school for craftsmen in Hamburg until September 1939, to prepare for emigration.

After that, he was subjected to forced labor: until November 17, 1939, he worked during the fall harvest in Lossow, in the administrative district (Kreis) of Lebus, and then was in a labor camp (Am grünen Weg) in Paderborn until April 1, 1940. Then, until February 28, 1943, he was sent to a labor camp (Am Schlosshof) in Bielefeld. On March 1, 1943, Paul Hoffmann was deported from there to Auschwitz, where he was taken two days later to the Buna/Monowitz concentration camp. In Monowitz, he was first assigned to do transportation and assembly work at I.G. Farben’s plant construction site. By February 1944, he had been in the infirmary a total of five times. From February 1944 to January 1945, the intervention of his friend Heinz Giesener, who was a Kapo, garnered him an assignment to clerical work in the costing office of the Buna plant. The office manager was Hans Schorr, an NSDAP member, who protected Paul Hoffmann and enabled him to survive. On January 18, 1945, the SS forced Paul Hoffmann and thousands of other prisoners to set out on the death march from Auschwitz, first to Gleiwitz, and then continuing on in freight cars to Buchenwald, where he stayed from late January until the end of February 1945. In late February 1945, Paul Hoffmann was sent for one month to the Holzen concentration camp in the vicinity of Holzminden in Lower Saxony, a subcamp of the Buchenwald concentration camp, where he did forced labor in an armaments plant. On April 10, 1945, he was forced to set out on foot again, heading toward the Flossenbürg concentration camp. On the evening of April 12, 1945, he managed to flee alone into the forest, and one day later he was liberated by American tank forces near Eisenberg in Thuringia.

After the war, Paul Hoffmann first became head of the commercial administrative department of a men’s underwear and shirt manufacturer, Herrenwäschefabrik Kaufmann & Sachs, in Bielefeld. In 1962, he moved with his wife and their two children to Düsseldorf. From 1962 to 1986, he was first manager and then administrative director of the Jewish Community of Düsseldorf. Until 1996, he served as executive director of the North Rhine regional association of Jewish communities. Paul Hoffmann died in Düsseldorf on February 11, 2008.

The story of his childhood and youth is told in a book by his son, Daniel Hoffmann, Lebensspuren meines Vaters. Eine Rekonstruktion aus dem Holocaust (Traces of My Father: A Reconstruction from the Holocaust).

(Daniel Hoffmann, son of Paul Hoffmann; transl. KL)