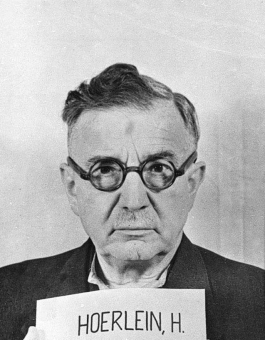

Philipp Heinrich Hörlein (1882–1954)

© National Archives, Washington, DC

“It is contrary to any experience in life and therefore cannot be accepted without concrete counter-evidence that a man who devotes his life to the welfare of humanity, who day and night reflects upon how he can ease the sufferings of his fellow men, can at the same time cold-heartedly do things or permit things which would make the purpose of his life illusory.”

Philipp Heinrich Hörlein was born in Wendelsheim in the Rhenish Hesse region on June 5, 1882. He was the son of the farmer Heinrich Hörlein and his wife, Philippina (née Dürk). After attending school in Alzey and Darmstadt, he began studying chemistry at the university in Darmstadt in 1900 and continued his studies in 1902 in Jena, where he received his doctoral degree in 1903. After that, he worked as an assistant to his dissertation advisor, Ludwig Knorr, until joining Bayer’s research laboratory at Elberfeld in 1909. There he was promoted rapidly: in 1911, he was entrusted with the supervision of the pharmaceutical laboratory, where he discovered the soporific Luminal in 1912. He was made an authorized signatory in 1914, a deputy director in 1919, and an alternate member of Bayer’s managing board in 1921. After the formation of the conglomerate I.G. Farben, he was made an alternate member of the managing board here as well in 1926, as head of pharmaceutical research in Elberfeld. The same year, the University of Munich awarded him an honorary medical degree and the title Dr. med. h.c.

From 1931 until the war’s end, Heinrich Hörlein was a full member of the managing board of I.G. Farbenindustrie AG and deputy director of Product Division II (Chemicals and Pharmaceuticals), under Fritz ter Meer. In 1932, he was awarded the state medal For Services to Public Health (Für Verdienste um die Volksgesundheit).

Between 1933 and 1941, he ran the Elberfeld plant, and in 1934 he joined the NSDAP. In 1941, Hörlein was named a “military economy leader” (Wehrwirtschaftsführer). His responsibilities, pharmaceutical research and the “search for pesticides and insecticides,” also included, by his own admission, the reporting of toxic substances produced by I.G. Farben to the Army Ordnance Office (Heereswaffenamt), where from 1935 on they were tested to determine their suitability as chemical agents. Under his guidance, the chemist Gerhard Schrader developed the highly toxic nerve gases tabun (1936) and sarin (1938) in Elberfeld and Leverkusen. Their effects also were tested in self-experiments on employees of I.G. Farbenindustrie. After I.G. Farben and the Heereswaffenamt had developed a process for making tabun on an industrial scale, a nerve gas plant was set up in Dyhernfurth near Breslau by I.G. Farbenindustrie.

Hörlein was arrested by the U.S. military administration on August 16, 1945, indicted in the I.G. Farben Trial in Nuremberg in 1947, and acquitted on all counts one year later; it could not be proven that as a member of Degussa’s supervisory board, he had been aware of the use of Zyklon-B and medical experiments in the concentration camps