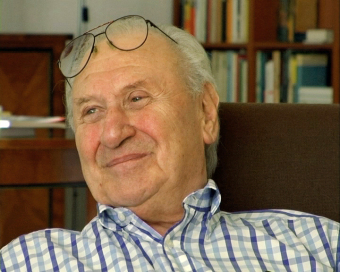

Siegmund Kalinski (*1927)

© Fritz Bauer Institute

“In comparison with Birkenau, Monowitz was a ‘sanatorium,’ as the prisoners used to say. By that, they meant that at least they had a sack of straw there that they could lay their head on, whereas in Birkenau they had to sleep on wooden plank beds, with 12 to 16 people squeezed into each one, in a horse barracks.”

(Siegmund Kalinski: “Erinnerungen an Menschen in der Hölle von Auschwitz.” In: Ärzte Zeitung, January 27, 2005, p. 2. (Translated by KL))

“I didn’t want to remember at all…. I would have liked to just block it out. I’ve lived in Germany for more than 25 years without saying a single word about Auschwitz; nobody knew anything, I didn’t want them to.”[1]

Siegmund Kalinski, the youngest of three children, was born in Cracow in 1927. His father, a liberal German Jew, ran a shoe store there. Siegmund Kalinski attended the Polish school and had many Polish friends, with whom he played soccer. After sixth grade, he was not longer allowed to go to school, because World War II had broken out: in 1939, there was an appeal for men to leave Cracow; he was separated from his family and fled with an uncle, traveling 600 km (372 miles) on foot through Poland. Not until September 1939 did he get back to Cracow, where he rejoined his parents. Their financial and legal situation deteriorated, and soon the Kalinskis had to sell all their belongings and move to the ghetto in Bochnia. His father was taken away in 1942 in the first wave of deportations, and his mother followed soon thereafter. He never saw his parents again.

Siegmund Kalinski had to do forced labor at the Cracow air base. His sister had been living in Palestine since 1935, and his brother went underground. Siegmund was deported alone to the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp, and a few weeks later, on Christmas Eve 1943, he was transferred to the Buna/Monowitz concentration camp. The prisoners had to wait outdoors naked all night long, at -20°C (-4°F), for the intake process at the camp. In Monowitz, he found three “veteran prisoners” who served as his mentors: Janek Grossfeld, Nathan Weissmann, Leo Diament. They procured “teachers” to instruct him in history and the natural sciences. Finally he got a job as a clerk in the electricians’ detachment. His friends’ escape plans were betrayed, and the three men were hanged with the entire camp population looking on. He escaped from the death march through Gleiwitz, Mauthausen, Sachsenhausen, Oranienburg, and Flossenbürg (Upper Palatinate region of Bavaria) that began on January 18, 1945, by floating across the Rhine in an empty ammunition box to the French Army.

After the war, he received the wartime high-school certificate (Kriegsabitur) in Cracow and studied medicine. He worked in Poland as a physician and journalist before emigrating to Austria in 1963 and to the FRG two years later. In Germany, he worked as a general practitioner and as a visiting lecturer at the Goethe University in Frankfurt am Main, and he continues to this day to be involved in the medical profession, serving on various committees. In 2008, he was honored with his profession’s highest award, the Paracelsus Medal. He was reluctant to talk about his time in the camp, and he did not tell his colleagues about it until the early 1980s.

(SP; transl. KL)

Siegmund Kalinski, oral history interview

(German)