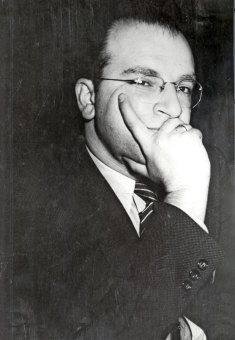

Norbert Wollheim (1913–1998)

© Fritz Bauer Institute

(Verdict in the Wollheim suit, June 10, 1953. HHStAW, Sec. 460, No. 1424 (Wollheim v. IG Farben), Vol. III, pp. 446–488, here pp. 480–481. (Transl. KL))

(Otto Küster, summation in the Wollheim suit, March 1, 1955. HHStAW, Sec. 460, No. 1424 (Wollheim v. IG Farben), Exhibits, Vol. II, 26 pp., here pp. 24–25. (Transl. KL))

“It’s not enough what you do for yourself. You have to try also to do something for people who are less lucky than you are or need your help and support.”

Norbert Wollheim was born in Berlin on April 26, 1913, as the son of Moritz Wollheim and his wife, Elsa (née Cohn). He and his sister, Ruth, born three years earlier, grew up in an assimilated Jewish family. After his Bar Mitzvah, he joined the Jewish youth movement and became involved in its social work. After graduating from high school in 1931, Norbert Wollheim studied law in Berlin, planning to become an attorney. After the National Socialists’ accession to power, however, he had to give up his studies. Starting in 1935, he worked for an iron and manganese ore company. In summer 1938, Norbert Wollheim married Rosa Mandelbrod. After November 10, 1938, 10,000 Jewish children were granted an opportunity to leave the country: By late August 1939, thanks to the trains of the Kindertransporte, 6,000 to 7,000 Jewish children from Germany were rescued and taken to Great Britain (and to Sweden), and several thousand more were able to leave Austria. To organize these children’s rescue missions, Norbert Wollheim worked almost round the clock in the Reich Deputation of Jews in Germany (Reichsvertretung der Juden in Deutschland). The task was exhausting, both physically and mentally: The organizers of the children’s transports had to not only look after the departing children, but also convey comfort to their relatives.

When the start of the war in September 1939 made emigration almost impossible, Wollheim trained for work as a welder until, in the wake of the “Factory Action” in March 1943, he and his family were arrested and deported to Auschwitz. At the ramp, Rosa and their 3-year-old son, Uriel, were sent to the gas chamber, and Norbert Wollheim was put in the Buna/Monowitz concentration camp to do forced labor. As of June 1943, he was assigned to a skilled metalworkers’ detachment as a welder, and this position allowed him to help his fellow prisoners. On the death march that began in January 1945, Norbert Wollheim endured three months of winter cold and hunger before escaping with two friends in April and finally being freed in Schwerin by American soldiers.

Norbert Wollheim settled in Lübeck and began immediately after the war’s end, as deputy chairman of the Central Committee of Liberated Jews in the British Zone, to champion the cause of the displaced persons (DPs). Moreover, he played a key role in the rebuilding of Jewish community life in Germany, though he himself had decided not to remain in Germany. He married again in 1947, and he and his wife Friedel (née Löwenberg) had two children. Norbert Wollheim testified as a witness in several postwar trials, including the 1947 I.G. Farben trial in Nuremberg and the Harlan trial in 1949. In addition, he used newspaper articles and public speeches to advocate commemoration of the victims, and tried to help make a change in public awareness in Germany. In 1950 he began his own fight for compensation: With his attorney, Henry Ormond, he filed suit against I.G. Farben in the Frankfurt Regional Court (LandgerichtFrankfurt/Main) in 1951. On June 10, 1953, the court ruled in favor of Norbert Wollheim on all counts and required I.G. Farben to pay him compensation in the amount of 10,000 DM.

(SP; transl. KL)