Defendant Walther Dürrfeld’s Slide Show at the I.G. Farben Trial

© National Archives, Washington, DC

The following statements by Buna/Monowitz survivors stand in contrast to Duerrfeld's remarks about the easy work of "pulling cables":

“The worst cases of frost-bite arose among prisoners working in the iron and cable squads. Work in one of these squads often approximated a sentence of death, as the strain imposed on the men was highest there.”

“One especially awful work detachment was the cable-laying squad. I myself saw the skin left on the cables by the prisoners, who had to work mostly without gloves or protective leather grips. I know that even the SS doctor said he was going to the I.G. to get these occupational safety items. It was to no avail.”

“I consider the cable detachment to be the worst in Monowitz. We walked in a narrow channel in the earth, one behind the other, and put the cable on our backs and hauled it on command. In the course of this we often were standing in water. We never had gloves.”

“Certainly, for some people, for example for me, the work in Monowitz was not so hard. For others, for instance the cable layers in Monowitz, it was very hard. That was our disciplinary detail. A man couldn’t stand it for more than three months.”

“I was an eyewitness watching how an Ingenieur VOGEL trampled on the head of an internee when they [sic] had fallen down while pulling cables. These comrades remained prostrate as our Kapo kept driving us on with a rubber tube. On one day we had 3 dead, which frequently happened.”

“Moreover, there was a a cable detachment that laid the heavy electric cables. This squad consisted of 500 to 600 men with a large number of master craftsmen and foremen. It was the hardest work detachment, since the prisoners always injured their shoulders, on which they hauled the cables. The engineers and Meister goaded the people on by beating them. I knew one of these Meister, because I once had reset his dislocated thumb, and I saw him throwing rocks at the prisoners in the ditch to make them work harder and faster.”

The “mistreatment by the I.G.’sMeister never stopped completely”: “Eventually the prisoners were asking the SS to protect them from the civilians. Once I made such a complaint myself. That was on the cable-laying detachment, around fall 1944, when I was the detachment clerk there. The cable detachment was one of the hardest at Buna.”

“I was also familiar with the cable detachment. The people had to take hold of the cables and pull them, or put them on their back and push. The prisoners used old rags for this work. The detachment was one of the most difficult. I don’t believe that the people didn't get hurt there, that's impossible.”

“At registration in Monowitz I was given the number 116,908. I was put in Block 3 and stayed there under quarantine for about two weeks. During this time I was busy working on construction in the camp. Finally I was assigned to the so-called cable-laying detachment, absolutely one of the most unpleasant work detachments in Monowitz. I stayed on this squad for about four months.”

“After a three-week quarantine, I was sent to the so-called cable-laying detachment. A lot of people died while working in this squad. Especially during the first eight weeks, there were dead to be mourned every day.”

“The new arrivals were immediately divided up into the hardest work detachments, such as the cable, cement, and coal detachments” and others. “The people from the cable-laying squad came to the hospital in the evenings with abrasions on their shoulders or hands.”

“In Monowitz I was put in the ‘cable detachment.’ Our job was to lay cable at the Buna plant. The squad was made up of about 120 prisoners and must have been the biggest work detachment in Monowitz. […] I spent about three weeks in the cable-laying detachment and then became a Stubenältester [barracks-room ‘official’] in the Monowitz camp.”

“I myself was assigned as an unskilled worker to Kommando 2, the cable detachment, along with my brothers Frank, Martin, and Elias. We rolled head-high reels of cable and pulled lead cables 5 to 10 centimeters in diameter to a new attachment site each time in the growing factory area. A little mistake, a tiny lapse could cost you your life or result in collective punishment: increased work time up to 20 hours.”

“The soil Kommandos were the worst of all: prisoners in these work gangs were made to dig ditches without having access to the proper tools. Then from a cable drum located about two kilometers away the cable Kommando laid cable in the ditches. The cable, approximately thirty centimeters in circumference and impregnated with bitumen, contained as many as 150 wires. The inmates in the cable Kommando simply couldn’t make any headway with such a heavy load on their backs. Blows rained down on them—so out of sheer necessity and with their last ounce of strength they somehow managed to pull the cable forward, millimeter by millineter. The daily mortality rate in this Kommando was, of course, extremely high. Max Stern, my father’s cousin, was assigned to the cable Kommando. Within three to four weeks he had already become a Muselmann.”

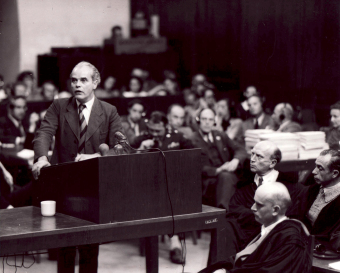

On April 15, 1948, Hans Seidl (Munich), a defense counsel in the I.G. Farben Trial at Nuremberg, called his client, Dr. Walther Dürrfeld, the former plant manager of I.G. Auschwitz, to the witness stand. The defendant was sworn in and then subjected to direct examination by his legal representative. In the course of his three days of examination,[1] Dürrfeld showed 50 slides (“a small collection of a former associate of mine”[2]) to the American tribunal on April 16, 1948; they had been introduced to the proceedings by the defense as Exhibit No. 133. The slides presented by Dürrfeld were a small remnant of an extensive collection of about 15,000 to 20,000 photographs and three color films documenting the plant construction in detail, and they had been left behind on the plant grounds of I.G. Auschwitz when the Germans abandoned the site. One purpose of the slide show was to give proof of I.G. Farben’s accomplishments in terms of building up the local economy in the eastern part of Upper Silesia, which had been incorporated into the Reich. Dürrfeld’s second objective was to show the U.S. military tribunal, in his defense, how civilized and agreeable the conditions on the I.G. Farben plant grounds supposedly had been for all the workers, including the concentration camp prisoners.

In his examination, Dürrfeld spoke of the “retarded state of civilization”[3] that the concern’s employees had encountered in the town of Auschwitz and the surrounding region. In March 1941, when Dürrfeld first inspected the place and the intended construction site, the more than 8,000 Jews of the small town—more than half its total population—had already been taken to the ghettos of Bendsburg (Będzin) and Sosnowitz (Sosnowiec). Dürrfeld found a community “free of Jews,” inhabited only by Poles and a few Germans; later it would experience a meteoric boom due to the influx of German workers and the building of a large I.G. Farben housing development. His work in the East, the Germanization of which was felt to be an honorable service to the fatherland, was interpreted by Dürrfeld as “war service,” and as an “armament job” as well as a “cultural function.”[4] Not only did a plant vital to the needs of the wartime economy have to be built, but the infrastructure of the town and the entire area also had to be raised to a level of civilization that was “appropriate” in the Germans’ view. That is, in the perspective of the German occupiers and their eager helpers from the war economy, it all had to be modernized in accordance with the standards of the Reich.

Dürrfeld’s vision glorified the achievements of I.G. Farben: according to him, the firm had brought employment to the people of eastern Upper Silesia. Moreover, he said, I.G. Farben had erected its huge plant in an effort made by a labor force enjoying equal rights and equal treatment, under difficult wartime conditions that worsened from year to year. He was especially intent on providing proof that the working conditions at the plant had been completely “normal” for everyone concerned, whether a civilian laborer, an “Eastern worker,” or a concentration camp prisoner. In his examination, he laid stress on I.G. Farben’s solicitude, regardless of the individual’s status. For Dürrfeld, the “civilian component,” whose interests the firm traditionally had looked after devotedly, also included the unfortunate concentration camp prisoners, whose lot I.G. Farben had striven to improve by providing them with employment in the plant and better food. As those in authority at the conglomerate conjectured, the Auschwitz prisoners preferred deployment at labor for I.G. Farben. Both the work at the plant construction site and the existence in the Buna/Monowitz “work camp” were, as Farben saw it, advantageous for the concentration camp inmates in comparison with the Auschwitz concentration camp (main camp) and the work detachments there.[5] According to Dürrfeld, there could be no question of inhumane treatment of the prisoners by civilians, much less of malnutrition and a high death rate. As he depicted it, even in a work squad that the surviving slave laborers described as a punitive and murder detachment, the notorious “cable detachment”, work proceeded smoothly and at a leisurely pace. Dürrfeld emphasized that every job was very easy if all the men were willing to work together as a team.

What the witnesses for the defense already had described in unison as they sought to deny the statements of the Buna/Monowitz survivors, Dürrfeld now tried to prove in black and white with his slide show. Everything was perfectly aboveboard and proper at I.G. Farben’s plant in Auschwitz, he contended. The firm, he said, had been a solicitous, socially responsible employer, seeking to implement an innovative large-scale project for both wartime and peacetime use, and doing so under extremely difficult wartime conditions, with the additional impediment of narrow-minded Nazi bureaucrats. The concentration camp inmates allegedly forced on the firm by command of the state leadership[6] were seen by those in authority at I.G. Farben as under-performing and thus also unprofitable and expensive workers, yet they were treated humanely by the chemical concern to the best of its ability, in its own assessment.[7] There could be no question of any “driving”[8] of the concentration camp prisoners on the plant grounds (work “at a run”). Like the concentration camp inmates, I.G. Farben, too—according to Dürrfeld—lacked influence and was powerless where the camp SS was concerned. If lives were lost at the I.G. Auschwitz plant and in the Buna/Monowitz camp, I.G. Farben—in the unanimously expressed opinion of the accused I.G. Farben employees and the defense witnesses—bore no responsibility of any kind for these regrettable occurrences. When questioned by his defense counsel, Dürrfeld tried to express how deeply affected he was by the prisoners’ lot: “When I saw inmates marching in groups or columns, when they moved to their place of work, when I saw these imprisoned human beings with their hair shorn off, clothed in an undignified uniform, [...] then I can only say that my heart bled.”[9]

Dürrfeld’s confidence in the success of his defense strategy was obviously considerable. To whitewash the conditions in the “cable detachment,” described emphatically as murderous by almost all the survivors, Dürrfeld showed the court two photos (Pictures 1322, 1323: “Cable operations”) of workers pulling cable, both pictures coming “from Ludwigshafen.”[10] The witness (or the defendant) believed in all seriousness that his presentation and the evidence produced would enable him to dismiss as erroneous the description given by the victim witnesses. Dürrfeld’s assessment of the affidavits made by the Buna/Monowitz prisoners came off as correspondingly critical: “[...] but as far as I can give an over-all judgment, I should like to say that in cases where I can judge the statements of the inmates, they are full of mistakes, misrepresentations, and enormous exaggerations. At one point it seems to me that the affiants themselves must have known that they were mistaken.”[11]

When confronted with Norbert Wollheim’s affidavit, which mentions welding without protective devices, Dürrfeld commented: “As to the statement that welding is hard work, I should like to refer to the slide showing a woman welding a pipe. We had many women, German and foreign, trained as welders, and I believe that as an engineer, I am in a position to judge that welding is not very heavy work. The women were glad to do the work.”[12] Dürrfeld’s comment on Picture 1318 reads as unintentionally comical: “One can again see that civilian workers and prisoners are working together. I am sure this is not a posed picture because you can see they are all busy and one can see that they are not especially hurried.”[13] The purpose of Dürrfeld’s statement that there was no hurry was to rebut the survivors’ allegation that many tasks had to be performed at a run, and that the pace of work was murderous for the weakened, half-starved prisoners. Seen in the right light, Dürrfeld asserted, the I.G. plant—contrary to the distortions and exaggerations of the prosecution witnesses—was a place of multinational concord, of peaceful harmony. Commenting on Picture 1326, which shows a plant workshop, Dürrfeld said, “In such workshops we had people of all nationalities working together peacefully.”[14]

Consequently, in Dürrfeld’s eyes the I.G. Auschwitz plant was a place of understanding among nations in the midst of war. “Excursions,” he said, had been made by the plants, “where the Belgians, French, and Russians met and entertained each other.”[15] As Dürrfeld saw it, the workers, usually labor conscripts and people forcibly brought from countries that had been invaded and occupied by the German Wehrmacht—countries whose economic power was being exploited in support of the German war machine—naturally had no grudge against I.G. Farben and its employees, but were delighted, as it were, to have been given employment.

Elsewhere in his testimony, however, Dürrfeld adopted a different note. In an incautious moment of self-revelation, Dürrfeld alleged that one of the subcontractors, a Belgian company, “according to its own admission, brought a lot of inferior human beings with it and we actually had a lot of difficulties with them. It is often hard to imagine what sort of people came to us. There were professional loafers and fakers.”[16] For this phenomenon, Dürrfeld had an explanation gleaned from his rich professional experience: “That is the consequence whenever such a lot of people are gathered and assigned to one spot without any selection being made. These people did not go through the selection process of an old plant which has an existence of 20 or 30 years.”[17] Then, using the language of his day, he continued unabashedly: “There were people who wounded themselves by heating 10 pfennig coins, then placing them on their body. Then they rubbed certain herbs on their bodies and, in this manner, were inflicted with certain diseases. Of course, all these things had to be eliminated.”[18] In the Buna/Monowitz camp, the SS, in concert with I.G. Farben, performed the “selection,” the “elimination” of the slave laborers who were “unfit for work.” Anyone who could no longer work, who could no longer be put into the camp as fit for work or deployed at the I.G. Farben construction site, fell victim to a selection. A “selection” of “skilled workers” based on I.G. Farben’s job specifications was made by Dürrfeld and others in the Auschwitz concentration camp (main camp) and in the Buna/Monowitz camp. Inside its corporate camp, I.G. Farben could command the concentration camp prisoners in its pay as it thought best. Prisoners who were no longer “fit” for a camp detachment (internal detachment) or for a plant detachment were “transferred” to the Birkenau extermination camp and murdered. Not one of those in charge at I.G. Farben, of course, admits to having had knowledge of this “selection procedure,” of this “method of elimination.” Whenever the reports of poor job performance started to pile up, Dürrfeld would stand at the camp gate with the SS leaders as the prisoner detachments marched out and pick out those prisoners who were in poor physical condition. Thus I.G. Farben had manifold options for maximizing inmates’ performance on the job. An “under-performing” prisoner could be reported to the SS, which selected the man in question at the next opportunity, or a representative of the firm could take part in the selection process.

(WR; transl. KL)