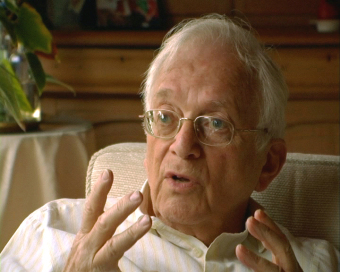

Freddie Knoller (*1921)

© Fritz Bauer Institute

© Freddie Knoller

(Freddie Knoller (with John Landaw): Desperate Journey. Vienna – Paris – Auschwitz (London: Metro, 2002), p. 189.)

>>b<< Freddie Knoller wrote about the time immediately after the war: “They [the French authorities] offered us food when we arrived, but we refused: Suddenly there was too much food! Ever since liberation everyone had been feeding us. They wanted us to be normal again. Like them, but we were not like them.”

(Freddie Knoller (with John Landaw): Desperate Journey. Vienna – Paris – Auschwitz (London: Metro, 2002), p. 214.)

“Every event in my story leads up to Auschwitz and no subsequent thought or action in my life is untouched by the memory of Auschwitz.”[1]

Freddie Knoller, born in Vienna in 1921 and the youngest of three sons in a Jewish family, enjoyed a sheltered childhood as a boy scout, stamp collector, and cellist in the “Knoller Brothers’ Trio.” After the Anschluss, the annexation of Austria in 1938, Freddie’s father, an accountant, got his sons out of the country: Private contacts helped Eric, the middle brother, obtain an affidavit for the United States; the oldest, Otto, got to England illegally; and 17-year-old Freddie was smuggled across the border to Belgium. He never saw his parents again, and after the war he learned that they probably had been murdered in Auschwitz in October 1944. After the German invasion, Freddie Knoller fled across the border to France in May 1941, but he was arrested and interned in the St. Cyprien detention camp. An outbreak of cholera there led Freddie to escape and go to Paris, where he scraped along, using false papers and working as a tourist guide for German soldiers in the Montmartre district, while other Jews were being forced to wear the star of David and the Gestapo started a series of arrests and deportations (les grandes rafles). To avoid this fate, Freddie escaped to southern France in July 1943 and worked for the Résistance. He was betrayed, however, and taken to the Drancy camp. From there, the SS deported him to the Auschwitz concentration camp on October 7, 1943.

Shortly thereafter, Freddie Knoller entered the Buna/Monowitz concentration camp. There he had to do heavy labor, first in the “cement detachment” and then in the “fitters’ detachment,” while receiving poor, meager rations. Thanks to additional food provided by Dr. Robert Waitz, a prisoner doctor in the infirmary, he weathered the trials and survived the periodic selections until the death march began on January 18, 1945.

His health somewhat restored, Freddie Knoller found his way to France and was reunited with his brother Eric, a soldier in the U.S. Army. He emigrated to America in 1947, and in 1950 he married Freda, a British citizen. Two years later the couple moved to England, where Freddie Knoller worked in the textile trade. Thirty years passed before he could talk about his time in the camps. His autobiography, Desperate Journey: Vienna–Paris–Auschwitz, was published in 2002. In vivid, powerful language, Freddie Knoller describes the almost unbelievable story of his flight through Western Europe and the terrible conditions of his imprisonment in the concentration camp. The book chronicles the experiences of the adventurous boy he was during the occupation of Europe, a careful observer, filled with the will to live.

(SP; transl. KL)

Freddie Knoller, oral history interview

(English)