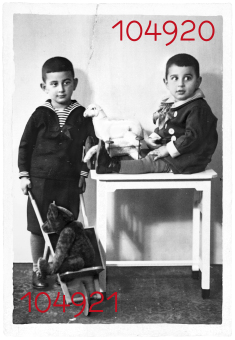

Hans Frankenthal (1926–1999)

© Fritz Bauer Institute

“Anyone who collapsed at work or tried to take it easy on the job was bullied, beaten, or kicked by the SS guards, the foremen, or the Kapos, many of whom were sadists and took pleasure in tormenting their fellow inmates. The civilian workers not only witnessed these atrocities, from time to time they even participated in them. And they also knew about the existence of the gas chambers at Birkenau. When we spoke with the civilians, they asked us if we thought we would get out of the camp someday. We replied, ‘No one has ever stayed there for good’ and then quoted the SS’s macabre quip: ‘Everyone gets out, even if they have to leave through the chimney.’ Everybody in Monowitz knew what was going on. The civilian workers, it seemed, simply accepted the fact.”[1]

Hans Frankenthal was born in Schmallenberg in the Sauerland on June 15, 1926, the second son of Max and Adele Frankenthal. His brother, Ernst, was two years older. Their father was a livestock dealer, and their mother, Adele, looked after the house and children. The brothers’ life was played out between school, farmyard, and local associations: the family was respected in the town, and Max Frankenthal was an official of the local rifle club. After 1933, their life was increasingly affected by restrictions, and the boycott of Jewish businesses on April 1, 1933, dealt a hard blow to the father’s livestock trade. “Proud to be a German Jew”[2] and a veteran of World War I, he still believed that nothing would happen to him. On November 10, 1938, Max Frankenthal was arrested by the Gestapo. His wife was forced to “sell” the family’s property to Nazis of proven loyalty. The father returned from the concentration camp a broken man. In summer 1939, the Frankenthals had to leave their “Aryanized” home and move to the cramped quarters of a “Jews’ house” in Schmallenberg.

In summer 1940, Hans Frankenthal had to leave school at the age of 14. He trained as a locksmith in Dortmund until the trade school was closed. Then, together with his father and brother, Ernst, he was made to do heavy labor, building roads, with inadequate food and poor accommodations. On February 26, 1943, the brothers were instructed to appear at the Gestapo office in Dortmund. There, the following day, Hans and Ernst Frankenthal saw their parents again and were led through Dortmund in broad daylight and deported to Auschwitz in cattle cars. Upon arrival, on March 1, 1943, the SS selected only the sons for forced labor in the Buna/Monowitz concentration camp; the parents were killed in the gas chambers of Birkenau right after arrival. The father’s last words were, “I won’t survive this; I’m too old. If the two of you do, go back to Schmallenberg.”[3]

Because of his training as a locksmith, Hans Frankenthal was put to work by the master craftsmen at I.G. Farben on building the plant’s supporting structure, putting large steel girders in place. Thanks to the help of the Communist block elder Eduard Besch, Hans Frankenthal was given the job of Stubendienst, responsible for ensuring the cleanliness of the block. Eduard Besch also put him in the masons’ school. Besch instructed him to make contact at the construction site with the Polish Volksdeutscher (ethnic German) Jan Krupka. Krupka smuggled letters, later even secret messages from the resistance, out of the camp. In summer 1944, SS doctors were doing medical experiments in the dental ward of the prisoner infirmary in the Buna/Monowitz concentration camp: they drilled holes in Hans Frankenthal’s healthy molars to test new filling materials. In addition, he suffered from serious abscesses on his legs, and only Eduard Besch’s help saved him twice from the selections. On January 18, 1945, Hans Frankenthal, along with his brother, Ernst, and thousands of other prisoners, was forced to go on the death march. In the Mittelbau-Dora concentration camp, he had to work in arms production. On April 3, 1945, Hans and Ernst managed to escape after an Allied airstrike, but three days later they were caught, turned over to the Gestapo, and sent to I.G. Farben’s concentration camp at the Leuna plant. They were deported from there once again in mid-April. During the transport, Hans Frankenthal lost consciousness and awakened several days later in Theresienstadt, after its liberation by the Red Army.

Abiding by their father’s wish, the brothers Hans and Ernst Frankenthal went back to Schmallenberg. The postwar years were difficult, partly because the citizens of Schmallenberg did not want to know anything about the extermination of Europe’s Jews and did not believe what the Frankenthals told them now and then. Hans Frankenthal married Annie Labe in 1948, and the couple had three children.

In the first Frankfurt Auschwitz Trial, Hans Frankenthal was summoned to testify in 1964: “[W]e were truly grateful that the trial was taking place. After 20 years, people were talking openly about Auschwitz for the first time.”[4] Hans Frankenthal took over the running of a butcher shop in the 1970s and built up a party catering service. After retirement, he again was active in the life of the Jewish community in Dortmund, becoming deputy chairman of the Auschwitz Committee of the FRG and a member of the Central Council of Jews in Germany. In addition, he was a member of the Association of Critical Shareholders of I.G. Farben. As such, he played an active part in the protests against the annual shareholders’ meetings of I.G. Farben in Liquidation, and spoke several times as an advocate for payment of compensation to the slave laborers of I.G. Farben.

Hans Frankenthal died in Dortmund on December 22, 1999.

(SP; transl. KL)