a “The Nazis’ power made itself felt, for example, in that more and more teachers lost their jobs and went to the Jewish schools to teach there. Professors from the university were trying to teach something to little children. In the parks, it was forbidden for Josef to sit on benches. Either he obeyed that rule or he had to watch out to make sure nobody caught him. At the swimming pool, where Josef took swimming lessons, there was a sign saying ‘Jews undesirable,’ but Josef still went there. Then it said ‘No Jews!’ and Josef still kept going there. The most unpleasant thing was the constant running. Outdoors, one always had to be careful. The boys from the Hitler Youth were always lying in wait somewhere, or other boys lurked on the way to school, waiting to beat up someone [...] Josef quit skating at the Engelbecken because it was too dangerous there. Josef learned to run faster and faster to avoid the rowdies. Once the boys caught him nevertheless and made him fight a non-Jew of his age. As an inferior Jew, of course he would lose. Josef, who couldn’t box, landed a blow on the nose of the Aryan, who also couldn’t box. The latter started to howl, and Josef managed to escape almost unscathed.”

(Stefan Keller: Die Rückkehr. Joseph Springs Geschichte (Zurich: Rotpunkt, 2000), pp. 13–14. (Transl. KL))

b “Had he not always listened to other people until now? First to his mother, then to his older cousin, Dolph. From now on, Josef vowed in the truck, he would listen only to himself.

”

(Stefan Keller: Die Rückkehr. Joseph Springs Geschichte (Zurich: Rotpunkt, 2000), p. 88. (Transl. KL))

“It’s a thing that nobody understands who hasn’t been in a concentration camp himself, Joseph Spring says: that you can keep adapting yourself there until you’re finally at a point where you think you’ll spend the rest of your life in the camp. You’re 100 percent convinced of it. Because you see the camp as nothing but the normal consequence of everything that has gone before it: the logical continuation of the years of persecution, the alleged inferiority, the humiliations since earliest childhood, since the first time you ran away from the Hitler Youths, the exclusion from the rest of humanity. The only thing good about life in the camp is that now it can’t get any worse. There’s only one more progression, the chimney – but then, when the bombs fell, there was suddenly a very, very tiny feeling of hope.”[1]

Josef Sprung, the first son of Polish Jews, was born in Berlin in 1927. His father died of blood poisoning when Josef was 5 years old. His mother, Czarna, supported herself and her sons, Josef and Heini, by running an ice cream shop, until it was destroyed in 1935. a Then she sent her sons illegally to relatives in Belgium, the Henenberg family. Until the Wehrmacht’s invasion in May 1940, they led a relatively secure life, but now they had to flee to France. Heini went into hiding in the home of a Catholic family, and Josef and his older cousin Dolph Henenberg finally obtained genuine French papers through the sponsorship of their landlady in Montpellier: Josef became “Joseph Dubois.” They found work as translators for the Germans and were doing relatively well. Dolph sent Josef back to Belgium to get his brothers, Sylver and Henri Henenberg. Using false papers, Josef brought them across the border to France, and the four tried to escape across the Pyrenees to Spain in October 1943. Finding the Spanish border closed, they traveled across France and tried to get into Switzerland near La Cure. They were caught while crossing the border and handed over to the Germans on November 15, 1943, under their true identities.

From the transit camp at Drancy, they were deported to the Auschwitz concentration camp. Josef’s cousins Sylver and Henri climbed onto one of the trucks when they arrived, and Josef never saw them again. He came alone to the Buna/Monowitz concentration camp b , where the clerk of the Political Department, Walter Peiser, offered to help him: He supplied food for Josef Sprung and directed Norbert Wollheim to train him as a welder. On January 18, 1945, his eighteenth birthday, Josef was forced to go on the death march. From Mittelbau-Dora he traveled farther westward, but developed infections in his feet and ulcerated lymph nodes. When he could no longer walk at all, he hid in a barn; he was liberated by the U.S. Army the next morning.

Since 1946, Josef, now Joseph Spring, has lived in Australia. He married Ava there and has two sons. In 1998 he instituted proceedings against Switzerland for complicity in genocide, but the suit was rejected. As a result, the Swiss historian and journalist Stefan Keller published Joseph Spring’s biography, Die Rückkehr (The Return), in 2003. Starting with the legal proceeding, there follow narrative flashbacks to Josef’s escape, arrest, extradition, and camp imprisonment, in a kind of “hearing of evidence,” ending with the verdict and the present day (2003). Keller linked the experiences, learned about in numerous conversations, with historical background facts and has the witness Joseph Spring take the floor, in dialogue form, from time to time. His vivid, direct way of speaking and his detailed, precise observations and memories lend clearness to the facts and convey an idea of what he went through.

(SP; transl. KL)

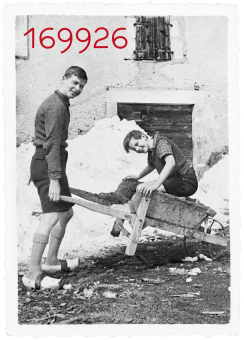

Photo Panel of Joseph Spring