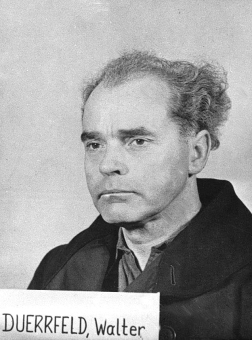

Walther Dürrfeld (1899–1967)

© National Archives, Washington, DC

“One thing is certain: the longer prisoners were used in our operations, the more their state of health improved.”[1]

Walther Dürrfeld was born in Saarbrücken on June 24, 1899. After graduating from high school, he was drafted for military service in 1917 and discharged in 1918. After World War I, Walther Dürrfeld completed an apprenticeship in metal working and then studied mechanical engineering in Aachen from 1919 to 1923. He received his doctorate in engineering in 1927 after interrupting his studies for two years to work as a production engineer. That same year he accepted employment with I.G. Farben’s Leuna plants. In 1932, he was promoted to head of the workshops for the entire high-pressure chemicals division. In 1934, he joined the Deutsche Arbeitsfront (German Labor Front), and in 1937 he became an NSDAP member and, as an “old pre-1933 glider-pilot instructor,”[2] he was named a Hauptsturmführer (equivalent of a captain) in the NS-Fliegerkorps (National Socialist Flying Corps).

In 1941, Dürrfeld was promoted and made an authorized signatory; Otto Ambros and Heinrich Bütefisch appointed him to serve as technical manager of plant construction for I.G. Auschwitz, and in 1944 he became the facility’s director and provisional plant manager. His former employees described him in their statements before the Frankfurt Regional Court (Landgericht)in the Wollheim lawsuit as a “person who championed all the concerns of the workforce, regardless of the individual’s position.”[3] His interest in the prisoners, however, was purely economic in nature; he negotiated in person with the commandant of the Auschwitz concentration camp, Rudolf Höss, for allocation of as many workers as possible

Walther Dürrfeld was unable to take the position initially promised him at Hoechst, owing to his anticipated prominent role in the incipient Wollheim lawsuit. He then became a member of the management board of Scholven-Chemie AG in Gelsenkirchen-Buer, the supervisory board of Phenolchemie GmbH in Gladbeck in Westphalia, and the supervisory board of Friesecke & Hoepfner GmbH in Erlangen. In the first Frankfurt Auschwitz Trial, no proceedings against him were initiated because of the provisions of the Transition Agreement. Walther Dürrfeld died in 1967.

(SP; transl. KL)

Defendant Walther Dürrfeld’s Slide Show at the I.G. Farben Trial