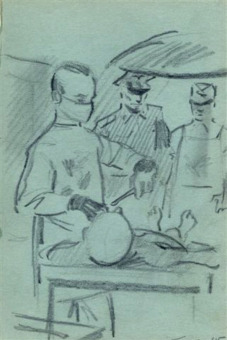

The Prisoner Infirmary in the Buna/Monowitz Concentration Camp – History and Setup

prosecution in the I.G. Farben Trial in

Nuremberg: In the prisoner infirmary

at the Buna/Monowitz concentration camp

© Serge Smulevic

Owing to their wretched working conditions, lack of protective work clothing, and completely inadequate diet and housing, the prisoners in the Buna/Monowitz concentration camp were highly susceptible to injury and disease. According to former inmate Dr. Robert Waitz, under “normal conditions” 90 percent of the Monowitz prisoners “would have to have been sent to hospital.”[1]

During the establishment of the Buna/Monowitz concentration camp in October 1942, no great significance was placed on the prisoners’ medical care at first. Only a single block was equipped as an “outpatient clinic” to treat minor illnesses. With the appearance of the first contagious diseases, such as typhus in December 1942, this proved to be wholly inadequate.

As of spring 1943, the prisoner infirmary (HKB; Häftlingskrankenbau) was successively expanded to create specialized wards: first, a block for infectious diseases and diarrhea (March 1943), an “internal ward,” and a general surgery ward (by June 1943). In addition, a dentist’s office, a surgical ward, and a general medicine ward were set up, and there was even a physical therapy area and a bacteriological research lab. Survivors also speak of a “hospital diet kitchen.”[2] By early 1945, the HKB had expanded to include nine barracks. The features of the rooms, in which the SS had invested little, were upgraded over time, however. From winter 1942/43 on, for example, there was a disinfection room for clothing.

After his appointment as camp elder of the prisoner infirmary in June 1943, the Polish inmate Stefan Budziaszek (Buthner) committed himself to expanding and equipping the infirmary. Among other things, he was concerned with building baths and washrooms in several barracks. The HKB staff tried to remedy the lack of devices of all kinds by stealing materials from the construction site, that is, from I.G. Farben, and having equipment assembled from the items in camp. For example, graph paper was used for temperature charts, and copper wiring, for makeshift instruments. An entire steam engine was even “organized” from the construction site.

The impression of comprehensive care is deceptive: In terms of its standards, the infirmary was far from meeting the requirements of a hospital. In addition to qualified staff and appropriate food, it also lacked basic medications and dressing materials, equipment, space, and beds. In 1944, the infirmary admitted, treated, and as quickly as possible released an average of 1,000 prisoners per week, so “that the SS doctors selected fewer sick and dying men for transport to the Birkenau gas chambers. At the same time, the prisoner functionaries increased the number of fellow prisoners receiving outpatient care from 300 at first to 1,300 in August 1944.”[3] I.G. Farben had assented only reluctantly to the establishment of an infirmary and now baulked at the notion of its expansion, so that beds often had to be shared by two patients, regardless of their respective illnesses.

During the evacuation of the Buna/Monowitz concentration camp on January 18, 1945, the last members of the prisoner infirmary’s team had to take along a great “part of the equipment, including the X-ray machine, which had been completed only a short time before, […] on a pushcart.”[4] After the death march, they were deported to the Buchenwald concentration camp, where they were freed by the U.S. Army. The approximately 850 patients who were not up to the impending march were left behind in the Buna/Monowitz concentration camp. The few who survived the following days with no support of any kind were freed by the Red Army on January 27, 1945. Many of them died in the weeks to come of the after-effects of imprisonment and disease, despite medical care provided by Red Army doctors and nurses.

(SP; transl. KL)